Into the Dungeon: D&D, OSR, DS, And Other Acronyms

Originally printed in CANDLE II (2022)

///

Music has always been important to me when playing a tabletop Role Playing Game (RPG). I can understand if this sentiment is not universal, but it always seemed odd to me as a player if the organizer didn’t play some sort of atmospheric music during a game. Are we going to sit here in silence talking without some sort of music to accompany us? How are we supposed to build drama against this deafening silence? As a player I had little choice in what others did in their games but when I started to become my own dungeon master (DM), I knew music was going to be my invisible player. Since the beginning of organizing my campaigns, music has been as important as the encounters, and its inclusion has given the players another dimension of the experience, which at the very least, helped me be a better DM.

My first tabletop group began with a few friends in a place where there was little to do but get together and play games. We began with a haphazard game of Dungeons and Dragons (D&D) 3.5, which was accompanied by assorted Spotify playlists. These nights over potluck and beers were woven together with premade playlists that would signal interludes of exploration and town music punctuated by dramatic combat music. We always considered these soundtracks, as rudimentary as they were, to be integral to whatever scene or scenario the party was encountering. Even though the reveal of combat was telegraphed by switching the playlist, music served as crescendo or lead up to action. D&D 3.5 is very combat based and, in fact, most of our sessions were centered around the inevitable lead into action. This is why epic movie scores from the 2000s or video game soundtracks from the 2010s worked so well, as they kept the tone of high action adventure throughout the session. They were filled with adrenaline and kept the momentum going through the very long combat sessions. Coincidentally, our music choice changed around the same time our group switched to a new world of games, Old School Roleplaying/Renaissance/Revival (OSR).

OSR is the reconstruction of tabletop roleplaying games that were present in the 1970’s and 1980’s. It is an intentional throwback to the simpler times of fantasy RPGs. Originally conceived as a reaction to the then rules heavy 3rd edition of D&D, OSR was a community driven set of systems that recreated the tone and structure of Pre 3rd Edition D&D. Beginning with systems such as Castles & Crusades in 2004 and the Old School Reference and Index Compilation (OSRIC) in 2006, OSR used actual rulebooks of older systems, clones of hard to find ruleserts, or an artful mix of the two. OSR was not only an attempt to go back and play older games, but also offered another dimension in roleplaying. OSR is the engagement of a system that existed before complications, where imagination was hoisted up by few rules and endless enthusiasm. This time fantasy also may or may not have anything to do with nostalgia as many people, including myself, have no connection with the actual time OSR recreates. It is a second layer of imagination and escape and could be a recreational recreation of nostalgia perhaps not even lived.

My group’s delve into OSR tabletops came with systems like Labyrinth Lord (a clone of the D&D Basic and Expert set) and Swords and Wizardry (a clone of the original D&D material from 1974-1978). We also play the collected D&D ruleset revised by Frank Mentzer often referred to as “Basic / Expert / Companion / Masters / Immortals” or “BECMI.” Our group loved new acronyms and we would use these acronyms to play new megadungeons with these systems or use them to play through original modules of the same era. OSR was a tool that had little rules for proper use and was more of an art in finding the right fit for your group. This was the same time when I started to find OSR zines, which provided community rules, discussions, and adventures that came in inexpensive publications. Many of these self published rulesets were PDFs that could be printed and put into countless binders, but some of them, like the Knockspell zine, could be purchased as a physical book. OSR, for us, was a chance to engage into the undercarriage of an RPG where nothing was really official but never really came close to being “illegal” due to the flexibility of the many companies’ Open Game License (OGL). Developers of new games were granted permission by companies like Wizards of the Coast to modify, copy, and redistribute some of the content designed for their games. This OGL, first published in 2000, led to not only the development of many of the OSR systems but also bigger games such as the Pathfinder RPG. Our group at the time were trying anything we could find, patching together rule sets and filling in gaps to make for a better personal experience. We felt, to the best of our knowledge, that we were successfully recreating a time of RPGs where games were a patchwork of house rules with written story prompts for flavor. OSR, for us, was a frontier of experiments that gave us new ways of interacting with a game both in a recreation and alchemical experiment.

Most of our OSR games dealt with dungeon delving or throwing our group into the exploration of the unknown that does not necessarily have a crescendo of action or even a balance of encounters. The Keep on the Borderlands, a 1979 adventure by Gary Gygax, the father of D&D, and second adventure in the Basic Ruleset, provided the foundation for the archetypal adventure. The players would be housed in a safe area, THE KEEP, and eventually venture out to explore the many CAVES OF CHAOS. This dichotomy between known safety and unknown danger provided the bones for adventure. Players would be thrust into the wild and charting the unknown would be essential to an understanding of the area. There might be sessions where all you do is explore empty rooms or caverns, while avoiding wandering monsters and making maps of the dungeon. Soon my group realized there was little need for bombastic scores to accompany mapping and avoiding wandering monsters. I feel our delve into OSR came at the same time we found another community of enthusiasts who were recreating yet another time period and offering it through Do it Yourself (DIY) channels, Dungeon Synth music.

Dungeon Synth (DS) is a style of at-home made fantasy synth. Despite it being a modern incarnation, its history is rooted in the 1990’s black metal scene, when its members created ambient synth projects and circulated those releases through tapes. These black metal side projects laid the groundwork for DS’ atmosphere and ethos regarding aesthetics, production, and distribution. DS is primarily a solo endeavor, with one person writing, playing, producing, and distributing the music. Today, it has become a diverse genre and industry, with tape labels, forums, festivals, and an international fanbase devoted to its history and development. Branching out from its beginnings, it now includes a spectrum of sound, transitioning beyond its dark ambient beginnings to a sound that includes neoclassical, new age, medieval, and even chiptune music. The space between fans and creators, since its beginning, has been small, leading to an intimate scene that exists today almost entirely on the internet.

While DS in 2022 comes in many sounds, the style and tone of the early revivalists in 2010 mimicked the work of the 1990 artists using droning explorations of lo fi ambience. Albums like Hedge Wizard’s More True Than Time Thought (2014) or Erang’s Tome II (2011) were used by our group as soundtracks to explore multi-level dungeons to the tune of ambient synth. Our eventual sessions through The Stonehell Dungeon or The Lost City were always accompanied by these DS records. DS was our foundation of sound when we did not need a cinematic score. DS was the sound of endless hallways and a slow plotting of maps. The music became the sound of The Borderlands, The Isle of Dread, and The Temple of Elemental Evil. The marriage between the music and our games felt so natural, and seemed almost destined that we would discover it at the same time. DS, for us, was the sound of magic and adventure not contained by an excess of rules. We would order tapes through the mail and get them at the same time our OSR zines were also being sent. We seemed to find two scenes that were operating on the fringes of the internet recreating an era out of time to the same tune.

While we never really thought of its connection at the time, our group would eventually discover the enthusiasm that DS had for OSR. This style of music almost seems couched into the fabric of fantasy RPGs, with either allusions or an active collaboration with tabletop games. Artists and labels, such as Vicious Mockery and Heimat Der Katastrophe, have dedicated themselves to providing soundtracks to independent and in house tabletop games. You could order tapes that would come with rule systems to play. Labels would send you dice to play with games that were printed on the back of the album. DS artists like Sword of Hailstone have created games we could use on the cassette holder, with an app to play through an adventure while listening to an album. OSR gave these musicians a reasonable system to incorporate into albums and they took it and created something wonderful. Because of the limited space, rulebooks are impossible to print, but simple systems like OSR are plausible for integration. We learned through time that DS and OSR were, in fact, lockstep in their community driven approach to a recreation of another time and place.

DS eventually provided the soundtrack to my own OSR game “Happenstance.” This game was a one page print and play you could cut out and laminate or fold up into a wallet. It was created out of a desire to play games at concerts, festivals, or at bars. This was also a dream that existed before COVID. Whether playtesting or demonstrating my game at conventions or metal festivals, I would play DS through my phone while explaining the rules. It was a small performance that added to the intimate experience. Not only could I talk about my own game that I was designing but it gave me a space to talk endlessly about this community of musicians making soundtracks to the proverbial dungeon crawls I was trying to create. I even bought a cheap portable tape player to play the growing tape collection I was getting through the mail for our games. There was a time I felt I was adding to the lore and living documentation of DS and OSR. While COVID has limited my time spent in crowds and the idea of public gatherings has changed, the strength of DS and OSR haven’t appeared to falter. Both hobbies seem to have very little rules on their execution and both seem entirely welcoming to people trying new things and shaping their own future, even in a world that has redefined what community is.

Dungeon Alignment: Recs For Character Creation

Originally printed in CANDLE III (2023)

///

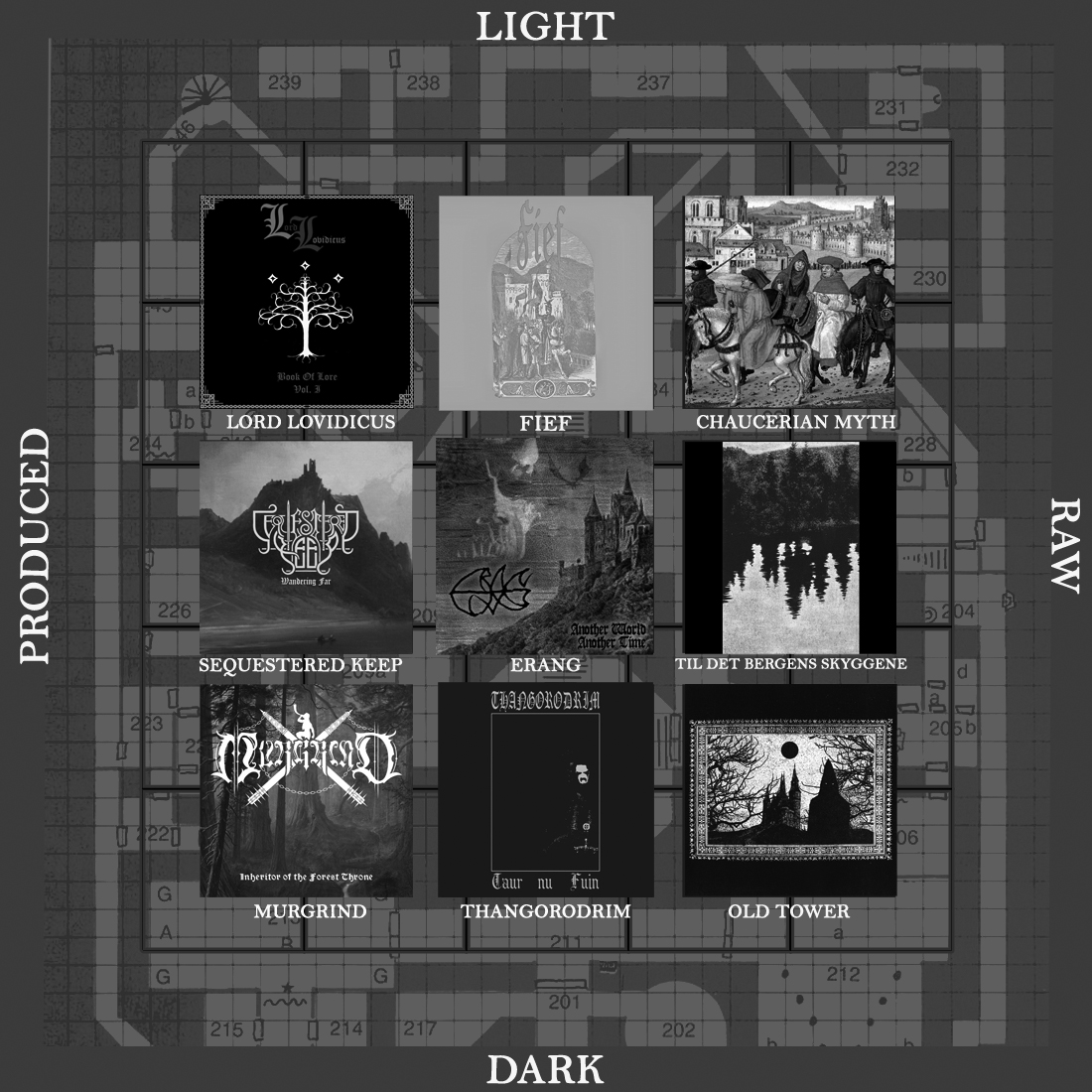

This is my second article on the at-home fantasy synth genre known as Dungeon Synth (DS). This article is for a publication that doesn’t really focus on micro-music, but I feel there is an invisible bridge between homebrewed tabletop roleplaying games and bedroom ambient synth. When talking to new people or writing primers for the style, I have used a nine point alignment chart for introductory recommendations. This DS alignment system especially made sense to people familiar with the Dungeons and Dragons (D&D) alignment system for character creation. Instead of the Lawful / Chaotic and Good / Evil axis, which is defined in the D&D chart, the DS alignment is between Produced / Raw and Light / Dark.

The alignment system for D&D was created in 1974 and has been refined over the years through its various systems. The nine point alignment system, created in 1977 with the release of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (AD&D), is now almost ubiquitous in our cultural consciousness due to many popular media having its characters placed within the nine points. Search any fandom with the words alignment and a familiar nine image grid on a black background will appear. By now many people are familiar with the idea of Lawful Good vs Chaotic Evil or Chaotic Good vs Lawful Evil due to examples being categorized or debated throughout the decades. Putting things into categories is a human desire that makes us want to do it even for fun.

The idea for a DS alignment chart came about on a forum made up of DS musicians and fans. Back around 2017, Russian artist RævJäger made an alignment chart that broke the music’s sounds into the two axes and came up with nine albums that typified each grid square. I honestly can not remember the albums that were used and, unfortunately, many of the posts are now gone. What stayed, however, was the idea of using the D&D alignment system as a tool for an introduction into the DS sound. I found it fun especially since DS and RPGs, particularly D&D, both shared common fantasy aesthetics.

DS is inherently morose but as mentioned before, the DS of the 1990’s was more monolithic in its bleak outlook than the revival period of the 2010’s. This grandfathered melancholy comes from its history with black metal, but as we march away from that period, DS opens up to new tones. This is why its revival period offers a gradation between its atmosphere as “Light vs Dark” is in relation to the overall tone of the album. Whether a tavern filled with gnomes versus a black castle in the deepest of forests, DS offers a spectrum of tones. This spectrum represents the holistic outlook of an album from sound, to style, to visual presentation. This is not a discussion of good versus evil, but rather what weight one will carry with them through the experience.

DS has and continues to be a bedroom style in terms of production. This is a cornerstone of the genre and has influenced much of its cultural currency in an age of the internet. People enjoy buying tapes from homebrewed musicians and in limited quantities. DS is a small operation and, for more than a decade in its revival period, has retained the charm of being a cottage industry. DS will inherently be minimalist to some degree. A maximalist DS without any footprints of its creator might be labeled as something else like new age, Berlin school, or soundtrack scores. This isn’t to draw genre lines or make delinations between professional and ameteur musicians, rather to stress the prevalence of rough production even in the most produced corner of DS. All of these albums will sound like homemade synth music and all of it will transport you to far away lands. However, some will wrap you in fuzzy tones more than others.

The nine albums chosen for this article’s image are to introduce the DS revival that began in 2011. DS has history stretching back to the 1990s, though its sound was not as nuanced as it is post revival period. These nine albums span from 2011 to 2017 and, for the most part, have been what I have used for recommendations. This will change, as the history of DS is being rewritten every day. These nine albums were the easiest ones to fit the alignment and are all albums that were recommended to newcomers. You are reading about DS in an RPG zine. This article comes without hyperlinks or embedded music players for you to sample the sound. You are on your own in terms of finding the music in this article. Below are write ups for each of the albums plus continued recommendations. It is now your adventure and you must choose your path.

Lord Lovidicus – Book of Lore Volume I (2015) [Produced/Light]

Book of Lore follows a line of better known releases from Lord Lovidicus. 2010’s Trolldom and Quenta Silmarillion are perhaps this artist’s most well known releases due to their placement in the early history of modern dungeon synth. Book of Lore sees the same focus on medieval fantasy but begins the artist’s ascent to the production the music deserves. Lord Lovidicus always wanted to sail in the cloud of production and, combined with the artist’s love for Tolkien lore, Book of Lore is fantasy ambient minus the rough edges. While the bedroom aspect is present, the music blurs between worlds with a sound that is approaching bliss. I could think of few other releases that quest for the same level of production that tries to transcend the bedroom setup.

Fief – I (2016) [Neutral Light]

Fief is a wonderful artist to start with in dungeon synth as it is a very popular sound among fans. In fact, Fief may be one of the most popular dungeon synth artists, which is no surprise given the string of amazing releases. Rather than a direct narrative, Feif’s five albums are vignettes into a medieval world that might or might not have any sort of fantasy elements. This is a long campaign in a low magic world that is filled with just as much danger and excitement as other more dragon-filled narratives. I feel Fief is popular due to both accessibility with the production as well as a charm in its minimalism. This is tavern music for the weary traveler and while there are few patrons, the hearth is warm and roaring.

Chaucerian Myth – The Canterbury Tales (2016) [Raw/ Light]

I have written a lot about Chaucerian Myth and the artist’s debut The Canterbury Tales. I wrote an introduction to the album for the CD reissue, which is on the inside flap. To put it simply, The Canterbury Tales was a watershed moment for dungeon synth as it took the growing modern scene and its bedroom recording, married it with English literature, and cast a drama into a 3.5 hour epic. An unofficial soundtrack to Chaucer’s collection of stories published in 1483, each of the tales is scored by the sounds of fantasy synth. The Canterbury Tales was a fantastic release from an active member of the Dungeon synth community, which set a new benchmark for intensity and devotion to the craft. In terms of atmosphere, there is little space between Fief and Chaucerian Myth. The difference lies in the length and scope of The Canterbury Tales, as these songs are cast in near 20 minute epics that wander sometimes lost in the tomes of history books. This is passion amid piles of books and its charm is undeniable.

Sequestered Keep – Wandering Far (2017) [Produced Neutral]

There is a joke among dungeon synth fans about the prolific, bordering on oppressive, release schedules some artists use. The years between 2015 and 2016 saw 14 releases from US based Sequestered Keep, which would have fit into this trope if not for the fact that all of it was outstanding. Wandering Far was the only release of 2017 and, for me at least, it was a grand declaration of magic and somber distance. Sequestered Keep aims in the same direction as Lord Lovidicus but collects the shadows as much as the highlights. Much like the album covers, Sequestered Keep offers rolling landscapes that are filled with as much joy as they are with sorrow. Sadly, 2018 would see the last release from this artist, so Wandering Far as well as the finale, The Vale of Ruined Towers are now monuments to the legacy of this artist.

Erang – Another World Another Time (2013) [Neutral]

For many, Erang was their first exposure to dungeon synth. This came through a compilation video put out by this French artist simply titled “2 hours 30 minutes of Dungeon Synth, Medieval Fantasy Music by Erang.” It was a simple video that provided 2 hours and 30 minutes of background music for reading, playing games, or whatever the user wanted. I feel there is something omnipresent about Erang as the music seems to touch every aspect of the sound. Another World Another Time catches the artist as they climb out of the classic dark ambient sounds of Tome I-IV to to craft a world of imagination and wonder. If I could offer any one record which I feel captures the variety in dungeon synth, it would be this. Additionally, 2013-2015 would see some truly fantastic works from Erang and this release is indispensable in one’s journey into dungeon synth.

Til Det Bergens Skyggene – Til Det Bergens Skyggene (2011) [Raw Neutral]

Til Det Bergens Skyggene is a German artist who is also the operator of Voldsom Musikk — a label specializing in black metal and dark ambient. Til Det Bergens Skyggene is a project that was responsible for 5 releases in a few short years before ceasing. The third and self titled release has grown in legacy in the dungeon synth scene for its reverence to the classic sound of the 1990s. With a focus on texture and ambience, Til Det Bergens Skyggene, the album, moves at a glacial pace across a landscape of fog with only shadowy outlines of trees and ruined structures. If limbo or the desolate landscapes of the afterlife had a soundtrack it would most likely sound like the track “Skog, Natt Og Stjerner.” This is a record that does not approach pleasantly and, in fact, it does not approach at all. Rather, Til Det Bergens Skyggene walks ever forward through the growing opaque wall of fog uninterested in anything but the crawl of time. It is aloof, magical, and completely uninterested in being accessible.

Murgrind – Inheritor Of The Forest Throne (2015) [Produced / Dark]

Inheritor Of The Forest Throne was the second record for Murgrind and a step forward in terms of production from the dark and classic sounds of 2013’s Journey Through The Mountain. Clear and grand sounds dominate the production, combined with a constant reminder of scorn and sadness. This marriage between the dark and production clarity was mirrored on the cover as it depicted a vast forest devoid of foliage and oppressive in its presence. Murgrind would set a new standard for production, and send a reminder to people that, despite the DIY nature of the music, professionalism and craft could still be revered.

Thangorodrim – Taur-nu-Fuin (2016) [Neutral Dark]

Taur-nu-Fuin was a monumental record on its release. I remember when it came out there was something that changed about the scene as its release pointed to a new benchmark for direction. With it’s cover, which worships the aesthetics of second wave black metal, to the sweeping labyrinthian sounds, to the obscure Tolkine lore, Taur-nu-Fuin was a champion of the classic sound that lay in the graves of Mortiis and Wongraven. With four songs and a running time of 50 minutes, Thangorodrim is intense in its need for commitment. This is not background music rather a passage into corridors that lay far out of the reach of sunlight. I would urge people to listen to this release for nothing else than to experience classic dungeon synth in a modern incarnation.

Old Tower – The Rise Of The Specter (2017) [Raw / Dark]

In terms of optics, The Rise of the Specter was perhaps one of the most famous modern dungeon synth records in the 2010’s. The Rise of the Specter’s cover was briefly used as the header for the 2017 Bandcamp article “A Guide Through the Darkened Passages of Dungeon Synth.” This was eventually changed to a more generic stone arch but, for a while, the hooded figure was a guide for newcomers into the world of dungeon synth. The Rise of the Specter and its ruminating sounds made sense for people as it worshiped the classic style of dungeon synth. This was Mortiis in 2017. This made sense as dungeon synth, for many, was the sound of dark passages and people in cloaks. It was mysterious and arcane and, above all else, dark. Old Tower was one of dungeon synth’s largest success stories as The Rise of the Specter led the artist to a deal with Profound Lore and a 2018 concert at the Roadburn Festival. Old Tower, for all intents and purposes, is the largest spokesperson for dungeon synth outside of its small community and to many, including myself, is the perfect spokesperson to the world beyond the small scene.

Continued Recommendations

Produced Light: Trogool / Рабо́р / Elador / Umbria / Kries

Neutral Light: Fogweaver / Secret Stairways / Utred / Gentle Fish Mumbling / Dwalin /

Raw Light: Chaucerian Myth: Comfy Synth / Hole Dweller / Sunken Grove

Produced Neutral: Verminaard / DIM / Nan Morlith / Nameless King

True Neutral: Hedge Wizard / House of Hidden Light / Mystiska Skogen

Raw Neutral: Jötgrimm / Grimrik / Amok Weg / Snowspire

Produced Dark: Barak Tor / Skarpseian / Splendorius / Elffor

Neutral Dark: Örnatorpet / Old Sorcery / Maradon / Faery Ring

Raw Dark: An Old Sad Ghost / Abandoned Places / Wallachian Cobwebs / MAUSOLEI /

Bardic Lore: Understanding Umbria’s Homecoming (2023)

Originally printed in FANTASY AUDIO MAGAZINE #1 (2023)

Homecomer might be a strange introduction to the Spanish artist Umbria. Its opener “A Long Journey Back Home” leaps into action with jaunty strings and rummaging bass notes which might subvert expectations to what dungeon synth sounds like. Yes, we expected tabletop RPG music but this is even more lavish, more like a play performed by troubadours around a campfire. We are then introduced to a character who is returning from a journey as indicated by the album’s title. No you are not late, this is the third act of that campfire play and you caught it right near the end. The text from the Bandcamp page for Homecomer heralds “Now the quest is over, and her homeland is calling from afar, deep within the Highlands. Finally, it is time to go home.” Homecommer is the end of a journey and much like other Umbria albums, it is a record which fits into a vague fantasy kingdom without borders. While it may seem like you need to go back and listen to earlier records, trust me it is the correct way to begin.

In 2012, fantasy author Glenn Cook commented on the lack of a map for his series The Black Company. “I took advice from Fritz Leiber who was my mentor and who said ‘don’t draw a map because if you draw a map, as soon as you start drawing the map, you start narrowing your possibilities’. As long as you don’t have a map you don’t have to conform to certain things.” In Cook’s series, there are still places named but to evoke a sense of uncertainty, especially given the military fantasy aesthetic, places are named but never put in distance. There is a constant fog of war which surrounds the characters and setting and place like “The Glittering Plains” or “The Forest of Clouds” retain this mythical quality as if they are fabled destinations. Locations when thought of this way become acquired knowledge and to get to them you had to follow the ones who knew. When talking to David, artist behind Umbria, he mentioned the same thing in regards to the unnamed world in which all Umbria albums take place. There is a place but it is purposely left unmapped. David enjoys the ambiguity of the created world and instead of organizing locations instead fills in the margins with bits of lore.

Homecomer tells the tales of a character returning from the same places which previous albums like The Sleeping Wizard or The Entombed Wizard call their setting. The protagonist is determined to reach her homeland but finds herself subject to mortal peril which will eventually be her unraveling. You can read the story by track with a paragraph each telling more of the story until the tragic yet accepted end. These stories in Homecomer are told over feature length tracks which all play like soundtracks to the dramas which inhabit the world. Homevomer is a complete story just started from a character we have just met and eventually will have to say our goodbyes. It is a somber tale but one that is filled with the joys and sadness of mortality.

Even though tags on Bandcamp are more impulsive than descriptive, the list of styles which are connected to Homecomer is fascinating.Dark ambient and dungeon synth are to be expected but more esoteric tags like baroque synth and folk synth are chosen to represent the record. There is little musician downtime in the world of Umbria as something is always starting and there will be little time to rest in droning spaces. The result is a unique take on fantasy synth which at times stretches into an ornate landscape of adventure which is the soundtrack to an imaginary tabletop RPG with each track being a keyed instance with its own character. “The Fog Cathedral” has bits of whimsical trickery in an otherwise brooding structure. “Night at the Minstrels Camp” introduced more silver tongue storytellers while “Across the Stone Forest” sees miles of untamed wilderness with secrets laying underfoot.

Dungeon synth is many things and despite some claiming the style to be one thing or the other, it really is whatever the person wants it to be. I have always thought of dungeon synth as magic and the artists weidling it in their own style. This could be from secluded wizards studying books to terrible swamp hags engaged in rituals to jaunty bards who weave illusions in the air with instruments. Umbria is that bard who has a wagon of mystical wares and plays their instrument by dramatic campifires while you rest. His melodies and stories weave into mystical worlds which play in front of your vision. While there is unknown danger in adventure, the dramas of Homecomer are never dark and the recountings of the mystical places visited never are accompanied with dread of regret. This record lives in safe harbor and much like that bard, the hero of the story will have her stories echo throughout history. The protagonist for Homecomer might die in the end (sorry for spoilers) but the legacy of her narrative will live on through these imaginary realms without names.

Postscript: I was later informed about another creator who designed an old school dungeons and dragons module based around the setting of The Sleeping Wizard. Designer D.D Grant created this free adventure as a love letter to not only classic D&d modules but also to the undefined places in the mind of Umbria. Perhaps we will see an adventure based around the world where now there is a lovely tree which was once a brave adventurer. I enjoy this creative extrapolation of tabletop games and dungeon synth as many artists also add in their own adventures. This is an instance where someone unrelated was inspired by the music. The entire thing feels like a collaborative project where everyone is excited and the whole thing feels like playing a game.

Kaptain Carbon is the custodian of Tape Wyrm, a mod for Reddit’s r/metal, Creator of Vintage Obscura, and a Reckless Scholar for Dungeon Synth.